Thursday 5 October, 2017

Urbanity and Rurality – The Bord na Móna Villages of Frank Gibney

Taken from: An Slean, Vol.1, No.12, December 1944, p.5.

So far as is known Frank Gibney had no formal planning or architectural training, although there is a suggestion that he started his career as an engineer in Dublin’s Balbriggan. Later in his life he became an associate member of the Town Planning Institute and in the 1930s he prepared town plans for Waterford, Tralee, Drogheda, Meath, Navan, and Tullamore, and is regarded, along with Patrick Abercrombie, Ernest A Aston and Manning Robertson, as one of the major figures of town planning in Ireland in the inter war years.

So far as is known Frank Gibney had no formal planning or architectural training, although there is a suggestion that he started his career as an engineer in Dublin’s Balbriggan. Later in his life he became an associate member of the Town Planning Institute and in the 1930s he prepared town plans for Waterford, Tralee, Drogheda, Meath, Navan, and Tullamore, and is regarded, along with Patrick Abercrombie, Ernest A Aston and Manning Robertson, as one of the major figures of town planning in Ireland in the inter war years.

In 1938 he made a submission to the inter-departmental committee on public works which proposed employment generating schemes, including the building of a Dublin Civil Airport, cleaning the Liffey bed, riverside promenades, cleaning public buildings, refuse removal, road widening, tree planting, creation of flower gardens and the construction of Clontarf Marine Boulevard.

During the War years he proposed a study toward a National Atlas dealing with the physical, human and economic aspects of the island as a whole.

Had Gibney’s career ceased at that moment it would have been a sad ending. Happily however his finest work was ahead of him, particularly in the 1950s when he became involved in the great Post War Housing Programme. During the years of 19511958 he was working for upwards of 16 different Local Authorities and producing designs for almost 300 houses per year, mainly in the counties of Laois, Cavan, Offaly, Louth, Kildare, Waterford and Kerry. This period of his work deserves a separate study and it is quite surprising as one goes around the country how one begins to recognize his distinctive style and realise that his work is everywhere. The better known examples are the very attractive little housing scheme at Clarecastle outside Ennis and the scheme in Ballinasloe on the Galway Road with its very imposing entrance gate flanked by circular towers.

Gibney had a very distinctive style of civil design deriving from the Beaux Arts tradition, the characteristics of which included circular ring-roads, radiating arterial roads, concern for the creation of prominent public buildings and their setting, all based on a very Structured and hierarchical approach. His style of planning and architecture also has echoes of the English Garden City Movement and contains references to the folk villages of the Low Countries and Germany of the 1930s, which I believe he visited in the inter war years. His plan forms are very coherent, but he was also a skilled three-dimensional artist who could organise spatial affects and all his designs show very sophisticated handling of space and the use of the various building types to give scale frequently punctuated by landmark buildings of unusual height or form.

The average permitted budget for housing in that period was £800 and he worked very skilfully within it by providing houses that have lasted extremely well to this day because of their good construction and also look quite well because of his insistence upon the provision of feature buildings or some design touches which elevated them above the ordinary run of Local Authority housing of that time.

This extraordinary workload was apparently carried out entirely on his own and I understand that he had only one assistant and produced most of the drawings himself which lends a certain coherence to all his work.

During the Emergency, reliance on native fuel was imperative and the midland bogs because of their proximity to Dublin with access by canal, played a great part in that drive. Before the era of mechanisation, the turf was cut and saved by manual labour and men from all over the country came to work for Bord na Móna and were accommodated in hostels throughout the Midlands. Wages were low at about £2 per week but for many it was a better alternative than the factories of war torn England. By the standards of the time the accommodation was comfortable. The food (three full meals a day) in particular was wholesome and the camaraderie was of a high order. The camps were well run and the remoteness of these hostels from town or city life created their own culture and for many, memories of the period evokes nostalgia.

In the post war years the accelerated development of the bogs for power generation and briquette manufacture commenced. This new approach with its heavy demand on mechanisation didn’t have the same manpower needs and in any case the men of the hostels were settling down and marrying and in order to hold on to this workforce more substantial houses were necessary. The decision was made to provide new housing schemes in appropriate locations to serve the turf development programme. In the event seven schemes were provided at Kilcormac, Rochfortbridge, Lanesboro’, Cloontuskert, Derraghan, Timahoe, and Bracknagh. Other proposed developments at Daingean, Cloghan, Littleton, and Timahoe North did not proceed.

Of these Derraghan is probably the odd one out because although it is a very well-mannered small scheme of 23 roadside cottages and though far in advance of many of the rural housing schemes that were constructed in that period; it doesn’t exemplify the characteristics which were to distinguish the other six schemes.

In these schemes we see the full flowering of Gibney’s ideas. The sources of inspiration are varied. The principal objective appears however to be a concern to create a sense of identity and place by means of architectural devises such as enclosure of space, civil axial planning, prominent urban buildings and a general sense of urbanity. This was obviously more important in the case of sites isolated from existing settlements, such as Cloontuskert and Timahoe.

I don ‘t know to what extent Gibney had control over the purchase of the land but in each case he came up with unusual, though appropriate plan form, to respond to even the most awkward site. Nor am I aware of the sequence in which the schemes were built – I think it possible that many of them were carried out together. In no particular order of development these were:

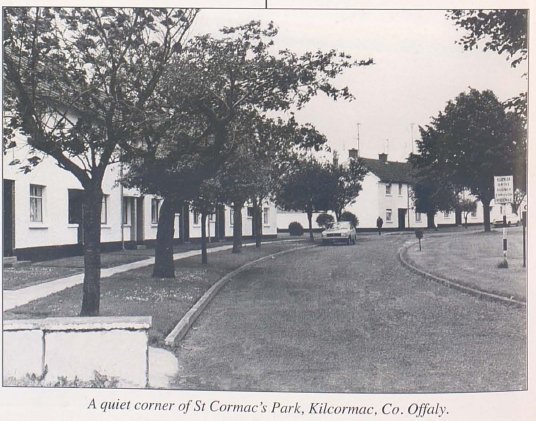

Kilcormac, Co.Offaly

This scheme of l05 houses is probably the best one to illustrate Gibney’s approach. Its plan form is based on three arcs of a gigantic circle pierced by a central axis. The buildings are disposed around the spaces to enclose them and the spaces themselves are of the most generous nature. The buildings are all provided in terrace form to create a sense of enclosure but are interrupted by feature houses and rear access lane entrances through arched feature buildings. Though it might be argued that the density of the scheme is wasteful, I believe that further houses were to be built at the rear of this site. The plans also contain a proposal for a rather attractive shrine on the central axis, but this wasn’t proceeded with. Though located on the edge of Kilcormac, the plan form of the development pays no heed to the village but like all of Gibney’s schemes, a very strong sense of internal identity has been created. Again, like all the schemes I have examined it remains in an excellent state of repair and maintenance which is a credit to the community.

Rochfortbridge, Co.Westmeath

This design of 98 houses is somewhat similar to Kilcormac and consists of two principal areas of open space, an entrance area dividing the scheme from the main Galway Road which spreads its arms out to welcome the visitor into the scheme, which is then linked by a central axis to a larger, five-sided open space surrounded by terraced buildings. The access culminates in a feature house containing an arched sitting area. There is a secondary access to a side road, which is reflected in an arched feature on the opposite side of the scheme. The landscaping of this scheme is of a high order and the general sense of identity and place is superbly achieved. It is probably the best known of these schemes because it is on the Galway Road. Again, because it lies well outside Rochfortbridge, there is no association with the village and the scheme proposes its own identity.

Lanesboro, Co.Longford

This scheme of 61 houses is within the village and acknowledges the existing settlement by lining up its central access with the spire of the church opposite. As in Rochfortbridge an entrance space is formed flanked by buildings, but this has the very unusual feature of a circular dwelling which is very much a landmark. Off this central axis is a loop road with single story houses grouped around it. As in all of Gibney’s schemes, there are no private front gardens (though there are extensive rear gardens) and the footpath is quite close to the front of the houses. I understand that in the transference of the estates to private tenants, the open space was left in the care of the Local Authority so that this characteristic of the schemes remains and has proved a very attractive feature as the grass verge flows uninterruptedly from house to house and gives the schemes an American or Continental feeling.

Cloontuskert, Co.Roscommon

This is one of the more remote schemes about three miles from Lanesboro’ and it contains 69 dwellings. Nevertheless it is probably one of the most urban of all and reminds me very much of the Dutch housing produced between the wars.

The characteristic elements of Gibney’s design vocabulary are very well expressed. An intervening area of open space separates the frontage houses from the main road and creates an entrance. A central access with an impressive tree-lined entry arrives at two symmetrical buildings which I understand were intended to be shops but are now boys and girls primary school blocks. Behind them is a site intended for a hall, but this was never constructed. As in Lanesboro, a loop serves the remainder of the scheme with the buildings set back on the bends to give a variety of spatial effects. The landscaping has matured delightfully and the general impression is of a distinct urban character in which it is hard to imagine that you are not in the centre of any city or town, but in deepest Roscommon.

Bracknagh, Co.Offaly

This scheme of 50 houses is my personal favourite. Here, the entrance road is flanked by two angled houses and makes a gentle curve into the scheme, arriving at a small very urban space defined by dwellings on three sides and with the unusual feature of a vertical building containing a shrine. This is attached to a local community hall and the scheme opens out into a teardrop shaped, substantial open space flanked by bungalows. The progression of curve into small open space, into larger open space, the whole anchored by the vertical tower feature is in the best traditions of housing layout and the variations of house types by the introduction of two-storied houses with an arched feature gives further variety. Possibly some more planting of the main open space would complete the picture.

Coill Dubh, Co.Kildare

This is the most substantial, the most remote and the most ambitious of all the schemes, containing 160 houses. It was built to replace a previous hostel. Of all the schemes, it was probably the nearest to a complete village in itself, containing schools and shops. Other facilities such as a church, etc. were not originally planned for but arrived later. Gibney prepared a master plan and sketched out the designs of the schools which didn’t exactly arrive as he had intended but otherwise his vision was fully realised. The plan form here is different from the others in being more organic and less axial but wholly successful. Again the device used in Rochfortbridge and Lanesboro’ of an entrance open space, flanked by buildings, is used, though it doesn’t lead to a central axis but meanders into the scheme opening to the left into a formal rectangle open space and then into a large central open space, vaguely rectangular in form, which opened south westward into an almost circular group of buildings around a little green and to the east on to another road access. The principal formal composition consists of an axis across the main open space, visually linking a most unusual four-story matched pair of shops with living accommodation over a feature building containing Christian and Islamic (crucifix and arch) devices on the far side of the green.

The tower of the school lines up with the vista through one of the arched buildings. The skilful way the open space flows through this scheme, now expanding, now contracting, maintains constant interest and the large central space, with its axis and strong feature buildings give a high sense or urbanity and identity. It must be one of the few modern examples in Ireland of the creation of an entirely new village.

Bord na Móna – A Unique Client

While Gibney’s work for Local Authorities was of the highest order, Bord na Móna was a unique client. It is said that the three characteristics for good civic design are a skilled architect, an understanding citizenry and a powerful and benign king. This combination gave us Leningrad, Central Paris, and Brasilia. In Todd Andrews Gibney found his Sun King and however they may have felt about it at the time, certainly the love which the inhabitants of these villages have subsequently lavished on their environment indicates their pride and satisfaction. The schemes are very much of their time and constrained as he was by the very tight budget, Gibney rose above those restrictions and working in the limited range of native materials available in those days of post war austerity, created a varied, high quality environment which looks as well today as it did 60 years ago. These schemes are a unique and unusual achievement and deserve to be treasured.

FERGAL MAC CABE, ARCHITECT AND TOWN PLANNER