Thursday 5 October, 2017

Footing the Turf

Taken from: Sceal na Móna, Vol.13, no.60, December 2006, p. 60-61

I chose the title “In the Wake of the Bagger”, for my novel of life in the Fifties and Sixties, knowing that it would have the desired air of mystery. Only those of a certain age, from a certain area of the country, would know what a bagger was. How the great are fallen! The hulking mechanical monster that created a social and industrial revolution in rural Ireland, that haunted our childhood imaginations, has lumbered off long ago into the shadows of history. And so has the stripper. Who now remembers the humble stripper? We had them on the bogs around Lanesboro’ when Stringfellow was still an altar boy! And the collector? The list goes on.

I chose the title “In the Wake of the Bagger”, for my novel of life in the Fifties and Sixties, knowing that it would have the desired air of mystery. Only those of a certain age, from a certain area of the country, would know what a bagger was. How the great are fallen! The hulking mechanical monster that created a social and industrial revolution in rural Ireland, that haunted our childhood imaginations, has lumbered off long ago into the shadows of history. And so has the stripper. Who now remembers the humble stripper? We had them on the bogs around Lanesboro’ when Stringfellow was still an altar boy! And the collector? The list goes on.

I was told once by someone from a “bog” background that her nightmares always centred on the dragline. I can see how someone could be terrorized by an out-of-control dragline, with perhaps a demented driver. Still it was the bagger that haunted my dreams and my imagination.

My family was one of the first to uproot and move to the Midlands when Bord na Móna offered not only jobs but also accommodation back in the 1950s. My father was a blacksmith in the townland of Killeenduff in Co Sligo. His trade was in decline as horses were being replaced by tractors on Irish farms. So he took the drastic decision to close the forge and seek a job elsewhere. He tried his luck in Dublin for a while but eventually got employment with Bord na Móna in Mountdillon, together with lodgings in the hostel right beside the service yard.

When he came back to Killeenduff for the occasional weekend he was full of stories of the men who were sharing the accommodation, men from all corners of the country. In the summer they were joined by hundreds of seasonal workers, students, casual labourers. My father was a Gaelic footballer and played for the Sligo County team. So it appeared that he and his mates played football every evening after work, trained, organized matches against other Works teams. And he told us about it all -many times. I’m sure 1 could name most of the men who played on the Mountdillon Works team in the 1950s if I tried: let’s see, the three Donoghues (unrelated) Paddy, Tom and Jim; three Paddys (also unrelated), Best, Kilcommons and Hanrahan, with my father thrown in, that’s enough for a seven-a-side anyway.

To secure the long-term services of their workforce, the Bord went on to build villages near the bogs. There were three such villages, or housing estates, around Lanesboro’ and my father was allocated a house in one of them, The Green. I have clear memories of travelling up in a hired lorry, crossing the Shannon, arriving in this newly built housing estate with all but two of the houses still empty.

I don’t know whether it was part of the Board’s intention, but the large families that moved into these houses provided the seasonal workforce they needed, and quickly replaced the casual workers and students who had previously flooded into the hostel every summer.

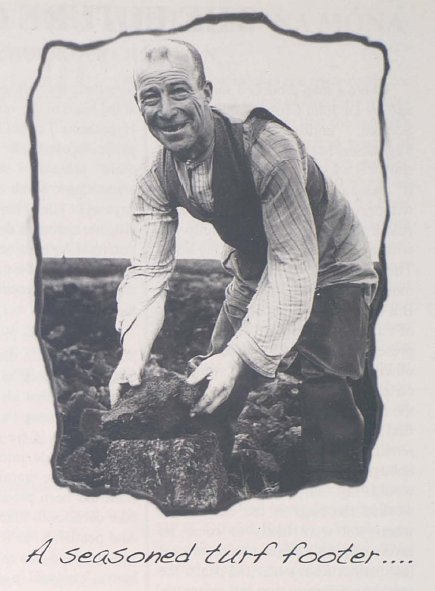

Footing the turf was the major task every year. The bagger left behind row upon row of sods, miles of neat rows, soggy, with the consistency of toothpaste. When they dried out they were rock hard, but sometimes over a wet summer they remained as soft as toothpaste. So the weather maintained a brooding presence over those summers, over the bog, over our lives.

I was out footing turf on the bog from the beginning, sometimes in Mountdillon, occasionally in Derryhaun, but mostly in Derraroge. The miles of spread turf were divided into plots. There were about sixty rows of double sods in each plot, a row stretching from the trench to the turf clamp, a distance of fifty to sixty yards. That was a lot of turf, but the rate for footing a plot was extremely attractive and was incentive enough to help us endure the backache and the tedium of such a repetitive activity.

It became a family occupation, and so our neighbours on the Green were around us on Derraroge bog all summer. A family or an individual would take a plot by setting up a few footings.

There was a number on each plot inscribed on the small lath that marked off one plot from the next, and the chargehand made a note of who took the plot. If the plot was good – dry sods well separated on an even bank – you could foot the turf easily and rapidly. Footing involved lifting the spread turf sods and building them into little structures that would enable them to dry fully. You placed two sods on the ground, a few inches apart, then laid two more crossways on them, continuing until you had built up five or six pairs in the structure.

But there were bad plots too. Where there was a soft spot or a dip in the bank the spread-aim of the bagger would drop the rows on top of one another, so that they were difficult to separate, and the wet ground would keep the sods from drying. Such a plot would take far longer to foot, and so you did your best to avoid it. The usual ploy was to head for the fire to wet your tea, and hope that someone else had taken it by the time you got back.

The fire was specially lit in the bottom of the trench and was maintained by a fireman. It was always a consoling sight to see the smoke of the fire curling up out of the trench -on windy days there was no fire allowed, and the fireman hoisted a flag instead. A barrel of water was placed near the fire, so you filled up your billy-can and placed it in the fire to boil, sometimes jostling with others for a hot spot. Tea, and indeed all food, tasted exotic on the bog, and was particularly sweet when you were killing time talking to the fireman or exchanging banter with other shysters.

Competition was intense and reputations were made at footing. Achievement could be measured in terms of rows or plots footed in specified time with callous accuracy. I and my family were at the bottom of that scale of achievement. The family team that excelled and put the rest of us to shame was the Gilmores. The individual who achieved legendary status was Ned Tynan, and his incomparable deeds are still recounted in awe. A heroic achiever of my own generation was Norbert Ward who pitted himself against the great Tynan and wasn’t so far behind even though he was a mere stripling of fifteen or sixteen years of age.

It must be hard for someone to imagine the appearance of the bog as it was then by looking at the deserts of milled peat on today’s bog-scapes. The proliferation of people, men, women and children, created the image of a great carnival. It being summer, bright shirts and dresses were visible for miles against the background of brown. The locos were constantly trundling up and down the tracks bringing wagon loads of turf to the tip-head where lorries were loaded mainly for the Dublin market. And if the weather was really good, the collector might be hard on the heels of the laggard footers, the phalanx of men in front of the long conveyor belt dumping in the footings.

But the busy bee engineers, who had created the bagger and the stripper to run in front of it preparing the bank, were hard at work inventing other machines to replace the labour force. The first to go automatic was the collector. There were rumours they were working on a machine to do the footing as well. But we scoffed – it wasn’t possible, footing would always have to be done by hand. Then this tractor with an enormous spiked drum appeared, and we knew they were serious about replacing us.

However, by the time the footing was eventually phased out the families had grown up. Children had become young adults with jobs or apprenticeships. Some were still following the well-worn path to England and two of my sisters settled for a while in London. But opportunities were opening up in Dublin and that was where I went. At one stage I had a flat near Clanbrasil Street and took great pleasure in going down to McHenry’s yard to buy my bag of turf. I saw the first of the turf and now I was seeing the last of it.

JACK HARTE.