Thursday 5 October, 2017

Early Days: The Kildare Scheme and the Turf Camps

Taken from: Sceal na Móna, Vol.13, no.60, December 2006, p. 70-72

The first real progress with regard to utilizing the bogs took place in 1933 when C.S.”Todd” Andrews became an official of the Department of Industry and Commerce and established cooperative tuff societies on a county basis to promote the production and harvesting of hand-cut turf and facilitate its direct sale by the producers. In that year 33 societies registered, followed by another 124 the following year. The societies met with varying degrees of success, but by 1940, 134 which had failed to make their returns were cancelled. In 1934 the Turf Development Board (TDB) had been set up to take charge of the societies. The new company was financed by grants and worked under the general direction of the Department of Industry and Commerce. Two events however occurred in 1935 which were to have a decisive influence on future bog development policy. Turraun peat works in West Offaly, which had been established in 1924 to produce machine turf, was handed over to the TDB by its founder, Sir John Purser Griffith, for the estimated value of its fuel stocks (£6,500). At the same time a delegation was sent to the continent to study German and Russian methods and its report recommended that the German system of machine turf production (similar to that employed at Turraun by Purser Griffith) be adopted, whilst the methods used in Russia should be kept under observation.

The first real progress with regard to utilizing the bogs took place in 1933 when C.S.”Todd” Andrews became an official of the Department of Industry and Commerce and established cooperative tuff societies on a county basis to promote the production and harvesting of hand-cut turf and facilitate its direct sale by the producers. In that year 33 societies registered, followed by another 124 the following year. The societies met with varying degrees of success, but by 1940, 134 which had failed to make their returns were cancelled. In 1934 the Turf Development Board (TDB) had been set up to take charge of the societies. The new company was financed by grants and worked under the general direction of the Department of Industry and Commerce. Two events however occurred in 1935 which were to have a decisive influence on future bog development policy. Turraun peat works in West Offaly, which had been established in 1924 to produce machine turf, was handed over to the TDB by its founder, Sir John Purser Griffith, for the estimated value of its fuel stocks (£6,500). At the same time a delegation was sent to the continent to study German and Russian methods and its report recommended that the German system of machine turf production (similar to that employed at Turraun by Purser Griffith) be adopted, whilst the methods used in Russia should be kept under observation.

On the basis of these recommendations the TDB acquired two Midland bogs in 1936 -a raised bog of some 4,000 acres at Clonsast in Co Offaly and a small mountain blanket bog at Lyrecrumpane, in Co Kerry. These bogs were cleared and drained and provided with railways, machines, workshops and offices. In January 1937 the Irish Press extolled the operations of the turf development at Clonsast, predicting that eventually one hundred thousand tons of machine turf would be obtained from there by a regular workforce of 600 men. The same report noted that the government was determined to develop Irish resources until the nation wouldn’t have to depend on outside sources for its fuel supply. The readers of the Irish Press could hardly have realized that soon this policy would become a significant necessity.

Labour supply, wage rates, hidden timber and sinking machines were some of the problems which were being encountered and overcome by the TDB when World War II broke out in 1939. By that time Clonsast Works had only received half of its compliment of turf cutting machines from its German suppliers but nevertheless machine turf was produced at Clonsast, Turraun, and Lyrecrumpane throughout the War years.

As well as making the purchase of machinery impossible, the War hindered the large-scale expansion of machine-turf output. Imported fuels were virtually unobtainable, so the energies of the TDB were devoted to overcoming the fuels shortage by producing large quantities of handwon turf for distribution in Dublin and the eastern counties. The most concentrated attempt to exploit the resources of the bogs took place during this period; thousands of acres of bog were purchased by the TDB and by 1941 around 1000 bogs were being worked in every county in the Republic. In 1941-42 a new element was introduced in the self-sufficiency fuel campaign, known as the “Kildare Scheme”.

The Scheme was set up to supply Dublin with fuel from an area covering 250 square miles situated between Enfield, Edenderry and Newbridge. One of the major problems was an inadequate labour supply in these areas so the answer lay in attracting workers from all over Ireland and offering them accommodation. Fourteen residential camps, each with a capacity for 500 workers, were built by the Office of Public Works and equipped with catering, sanitary and recreational facilities. The camps set up in north Kildare and east Offaly were located at Killinthomas, Shean, Lullymore Lodge, Drummond, Allenwood, Corduff 1, Corduff 2, Corduff 3, Robertstown, Newbridge and Edenderry. Todd Andrews described the firm of caterers which had been hired to handle the food supply as being hopelessly inadequate and the TDB was forced to take on the job of producing 12,000 meals daily without any knowledge of what was involved. Guidance was sought from the army, but their advice proved unhelpful and Andrews remarked that “the daily rations of a soldier were no more than a daisy in a bull’s mouth to men doing eight hours a day of heavy bog work”. After a few months of occupation the camp buildings were reduced to conditions more typical of refugee camps, due mainly to the lack of proper regulations and internal camp discipline. With the appointment of Bill Stapleton, a man who had experience of this type of industrial colonization, radical improvements took place. As chief hostel supervisor and catering manager Stapleton set about organizing the running of the camps on more socially acceptable lines. Rations were virtually doubled, trained cooks and kitchen staff were hired and orderlies appointed to serve meals, make beds and clean up generally. A proper medical service was provided, with a medical orderly based at each camp, concerts were organised together with theatre and football competitions, and each camp was provided with its own library. Fear of ecclesiastical disapproval prevented the TDB from employing female help in the camps for a number of years. However, due to the type of outdoor work associated with the turf industry, women workers were always very much in the minority.

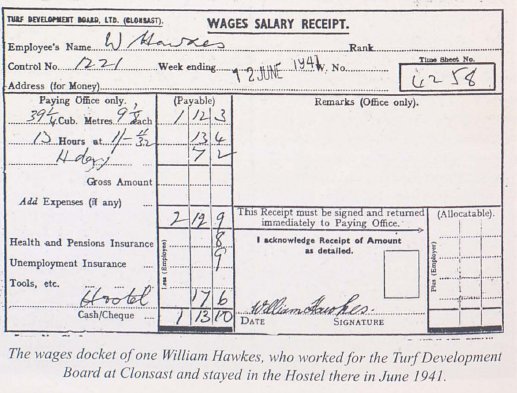

In the summer of 1942 agricultural and turf workers both received 33 shillings a week, but following a series of strikes by turf workers in 1942, Hugo Flinn, The Turf Controller, increased their wages in 1943 to thirty eight shillings. As turf workers were often on piece-rates they could earn extra money and have more free time than agricultural workers, so many labourers preferred to work on the turf schemes. The work was very strenuous however, and the men earned their money by the sweat of their brow, draining the bog and handcutting the turf. A report in the Leinster Leader in May 1942 tells of 140 workers from Dublin arriving in Edenderry in five GSR buses on a Monday morning and they were cheered through the streets as they made their way to the camp, formerly known as the Edenderry Union. Men from Galway and Mayo were already living there. Nine of the Dublin men after experiencing about an hour’s work on the bog, gathered their belongings and started walking back to the city on Tuesday, a journey of 37 miles, and seventy-five left the following Wednesday.

Workers received free travel vouchers to come to the camps, but if they left of their own accord, or were dismissed, they had to find their own way home. The remainder of the Dublin workers, as well as the men from Galway and Mayo, gave notice of their intention to leave at the end of the week unless conditions improved. The sample day’s ration for a turf worker, which was displayed in the Oireachtas restaurant that Wednesday, was as follows:

“Breakfast: two rashers, one egg, two large potatoes, six slices of bread and butter.

Lunch: Slice of beef, one egg, and six slices of bread and butter.

Dinner: a chop, vegetables, and eight potatoes.”

Reporting on the Dublin men still in the camp, the TDB engineer said he thought the majority of them were willing workers but very unfamiliar with bog work and that it would be some weeks before anything like an economic output could be expected from them.

At Newbridge, the military barracks, which for over a century had housed the cavalry and artillery units of the British Army, was leased by the Board of Works to the TDB for use as a workers’ camp. Newbridge housed and fed about 600 men who were transported to and from their work at Ballyteague, Allen, Clongorey or other neighbouring bogs by lorry each day. The accounts staff which was needed to deal with the large workforce, not only in Newbridge but in the other Kildare camps were housed at the barracks and dances and parties were occasionally held in what were the old artillery dining halls. All the bog tools such as the shovels, sleans, and rubber boots were stored in the old barrack prison and sports competitions were held each year on what was formerly the barrack parade ground. By 1948 both the workers and office staff at Newbridge were transferred to new Works hostels which had been built at several of the local bogs and the main barrack blocks were demolished in two stages during 1948-9 and later in 1975.

Not all the camps were located in existing buildings, some were purpose-built such as the one at Corduff south in County Kildare (later called Timahoe South), built in 1942. It comprised of twelve billets; six on either side of a field which was used as a playing pitch. The camp contained a cookhouse, dining hall, recreation hall, kitchen and orderly staff billets a camp office, a superintendent’s quarters and a small mess room. There was also a shower room and a drying room, which consisted of a billet with a couple of large stoves and shelving where the men could dry their clothes. In each billet there were 24 beds with army-type trestles and bed boards, a mattress, four blankets and a pillow. There was a stove in the centre of each billet principally for heating, but it was also used for making a can of tea or frying a pan of sausages and rashers. These snacks were necessary as there was a strict rationing system maintained in the camps because of the emergency regulations.

The TDB magazine, An Slean, provides an insight into life at the camps and the interaction between the various camps and the local towns. Tug-o’war’ and inter-camp races were prevalent as were hurling and football matches with local teams. An annual turf cutting competition was held between the camps and this was a big occasion since great rivalry existed between the different camps and winning this title was held in great esteem.

Improvements in general conditions, like replacing the old bed boards with spring mattresses, refurbishing the recreation halls, and the provision of a mobile cinema, were described in the magazine in glowing detail. Accounts were also given of the other forms of recreation available in the camps. These include, for example, the Radio Eireann Question Time Competition, which was broadcast from the Odeon Cinema in Newbridge in December 1944. Two teams of six people – representing Newbridge and the TDB, took part; the eventual winner was one of the Newbridge contestants. Irish classes were organized in the camps where it was decided that simple everyday phrases should be taught and that grammar should be introduced gradually. Sufficient textbooks were purchased to enable the distribution of one book between two men.

Interaction between the camp residents and the local communities was quite developed. In December 1945 the Leinster Leader carried a report of how the Rathangan Dramatic Society staged their play, “Paid in His Own Coin” to a capacity audience at the Allenwood turf camp, and in June 1946 the TDB Players were the winners at the Droichead Nua Drama Festival with their presentation of “The Down Express” and they later brought their play on a successful tour the camps. Dances were often held in the camps: An Slean carries an account of a dance held in Corduff camp where “the fair sex was very well represented – some coming from as far away as Sallins, Clane and Naas”. Many of the workers frequented the local bars at weekends and during periods of bad weather. A story appeared on the Leinster Leader about two Kerrymen who had consumed a quantity of drink and on their return to the Robertstown camp for their evening meal objected to the food and caused a minor riot. Potatoes were thrown about, furniture upset, windows were broken, the tables went up in the air and the Gardaí were called in to restore order.

The Kildare wartime Emergency Scheme ended in 1947 and despite initial labour and organisational problems, it worked well. Between 1942-47, over a half million tons of hand-won turf were delivered to Dublin. This turf was transported partly by canal, partly by train and partly by army lorries and stored in what used to be called the “Long Straight”(from the Grand Prix racing days) in the Phoenix Park. The Long Straight then became known as “the new bog road”.

MAUREEN GILL-CUMMINS.